Purpose

Discover Yoti's B Corp Impact Report

We’ve reached a full decade of being a B Corp! At Yoti, we believe technology has the power to create a safer, fairer and more trusted world. But as the world of technology evolves, we know we must remain mindful of how we do business. As part of our commitment to balancing profit and purpose, we’re thrilled to announce the release of our new B Corp Impact Report. It highlights our progress and impact in the areas that matter most to our stakeholders, our community and the planet. Highlights include: Improving the accessibility requirements of

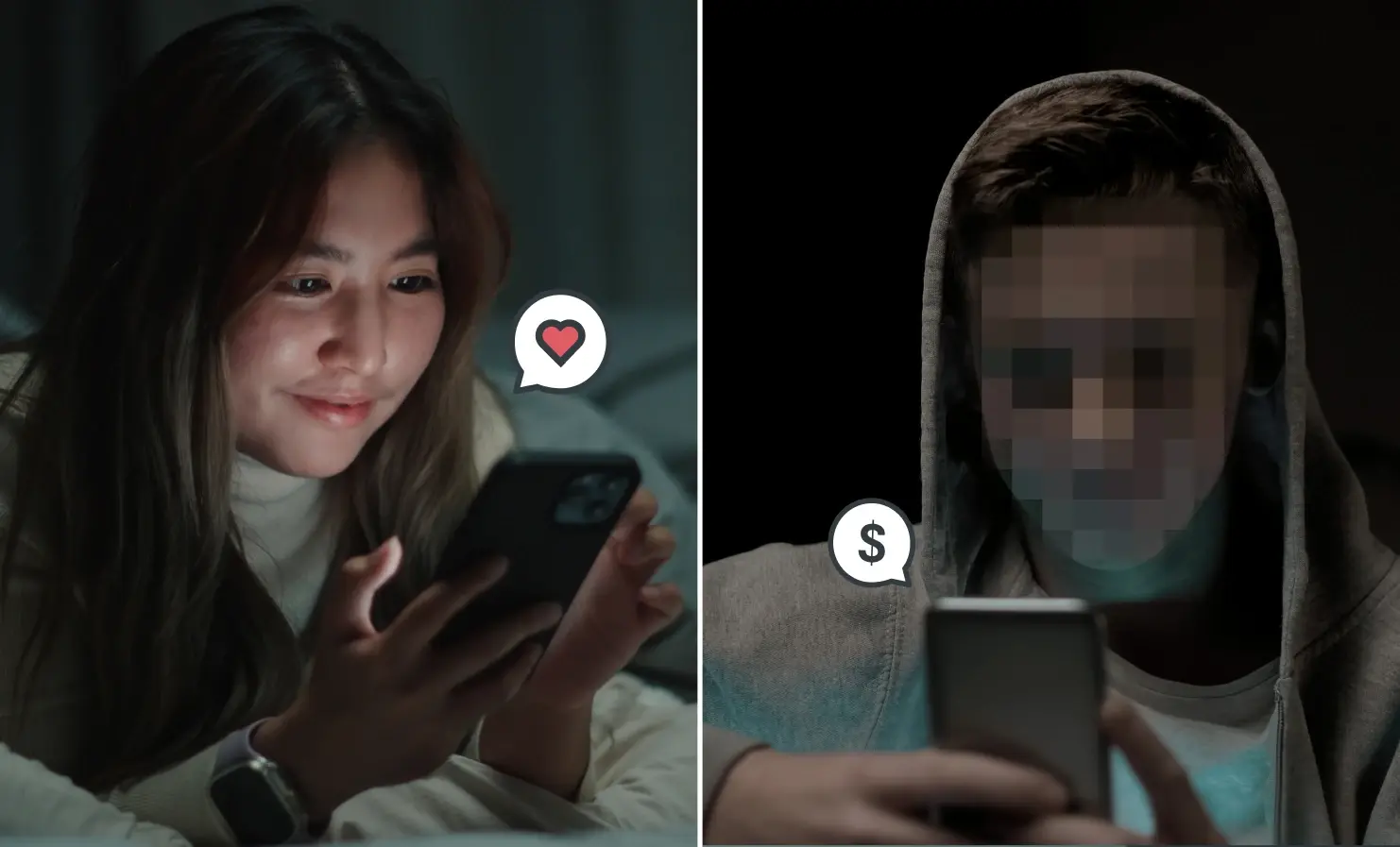

Protecting your heart and wallet: understanding romance scams

It is said that love makes the world go round. But as genuine daters are looking for love, there’s a growing risk of falling into a scammer’s trap. In this blog we explore the impact of romance fraud, common tactics used by fraudsters and how daters can protect themselves in their search for love. What is romance fraud? Romance fraud occurs when a scammer uses a fake profile and false identity to trick unsuspecting people on dating sites. They usually do this for fraudulent reasons and financial gain. The fraudster will often go to great lengths, convincing

The importance of transparency for facial age estimation

To protect young people online, businesses need to provide age-appropriate experiences for their users. This could apply to online marketplaces, social media networks, content sharing platforms and gaming sites. But to put the correct measures in place, businesses need to know the ages of their customers. It was previously thought that the only way to confidently establish a user’s age was with an identity document, like a passport or driving licence, or checks to third-party databases such as credit reference agencies or mobile network operators. However, regulators are now recognising facial age estimation as an effective alternative. As with

Making age checks inclusive

In today’s world, we can access a range of goods, services and experiences online. As a result, regulations are being passed across the globe to ensure that young people safely navigate the digital world. From the UK’s Online Safety Act to age verification laws in the US, platforms are being required to check the ages of their users. To do this effectively, the age assurance methods offered must be inclusive and accessible to as many people as possible. Why can’t businesses just use ID documents? Most people tend to think of age assurance as checking a person’s age

Say hello to our 2024 B Corp Impact Report

We’re delighted to reach our ninth year of being a B Corp. When Yoti was founded 10 years ago, we knew that we wanted to do business the right way. Because that’s the only way we can truly make the digital world safer for everyone. Our founders knew that in this industry, we were going to come up against some complex ethical questions. Working with identity, personal data and biometrics is a delicate matter. And that’s one of the reasons we became a B Corp – to hold us accountable to all our stakeholders including our people, clients, suppliers, the

Addressing social challenges: How eSignatures can help solve everyday problems

Our purpose is at the core of everything we do. Our principles are integrated throughout our business, whether that’s how we go about our day-to-day operations, interact with one another or design and build our solutions. This series looks beyond just how our products can benefit businesses. It also explores how they are helpful to the people using them. This article focuses on eSignatures. Tackling fraud People are becoming more aware and better informed of the different types of scams out there. So fraudsters have had to respond with new and increasingly complex techniques. In turn, people and businesses