As we go about our social purpose work we regularly get to speak to local, national and international non-profit organisations. Over the years, we’ve found that many struggle to understand the many ways digital identity solutions might help them in their work.

As part of our wider efforts to help the sector make sense of the technology, today we’re publishing the fifth of six articles looking at the use of digital identities in six different humanitarian and environmental settings.

Please note that, while the technology use-case is real, the scenarios are hypothetical in nature, and the projects do not exist as stated.

Location

Kenya

Scenario

Maternity and childcare clinics

Background

According to the World Health Organisation, 60% of mothers in sub-Saharan Africa give birth without ever consulting with a healthcare worker. This leads to an increase in the likelihood of complications that can cause maternal and child death.

In Kenya, in particular, the mortality rate of mothers during pregnancy and childbirth is considered to be high and was given as 342 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2019. The reason for this is that many women live in rural areas where there are no health care clinics and they can therefore not access antenatal guidance or the help of trained health professionals.

Transport to clinics in larger towns is also costly and this adds to the likelihood that pregnant women in Kenya will be unable to consult a health care worker for assistance.

UNICEF states that “The causes of maternal death are mostly preventable”, and links decreased maternal mortality with regular attendance at an antenatal or primary health care clinic.

Historically, Kenyan women had to pay a fee to attend a maternity clinic and this added to the inaccessibility of these services to the average mother-to-be. In 2013, the Kenyan government implemented a Free Maternity Service policy which resulted in an increase in the number of women who attended maternity clinics. In addition, Kenya has made great progress in recent years in institutionalising community primary health services.

Numerous small maternity clinics have been established in rural areas, usually with the help of NGOs, donors and other stakeholders such as UNICEF and USAID. Trained nurses and midwives at these clinics focus on educating mothers-to-be about nutrition, childbirth and hygiene, and on assisting and supporting during the birth of the baby.

Challenge

With maternity clinics and antenatal services more accessible to Kenyan women than ever before, there has been a significant increase in the number of women seeking to register at these facilities.

However, many of the women have no documentation and are unable to identify themselves officially. In rural communities, children are mostly born at home and their births are not recorded in a hospital.

This means that many people in these communities have no birth certificates. In Kenya, a birth certificate is needed in order to apply for a national identity card which is, in turn, required for a biometric identity number – known as a Huduma Namba, or “service number” in Swahili. Rural women may therefore remain undocumented, along with millions of others in the Kenyan population.

Solution

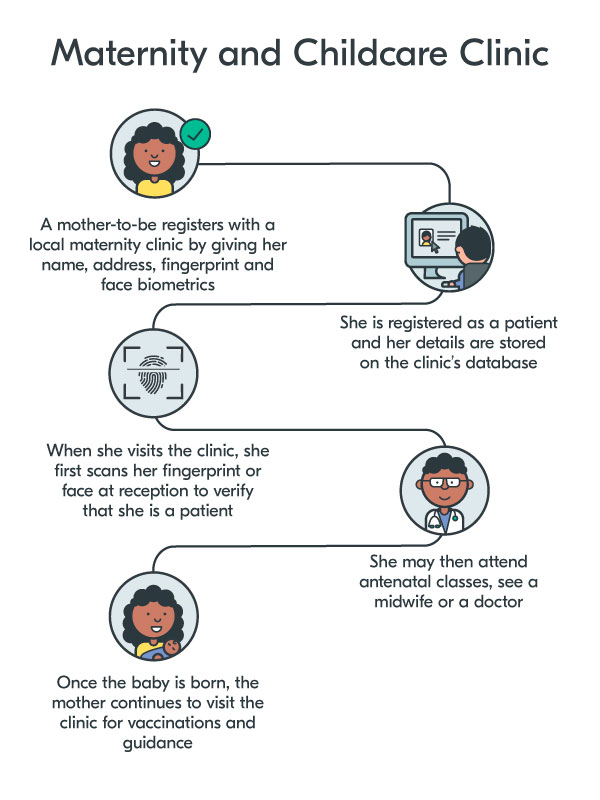

A maternity clinic could register pregnant women who wish to make use of the antenatal and health care services offered. Registration would involve recording a woman’s name, address details and any other relevant information, along with a scan of her fingerprint or face.

This is the same technology currently used by the Kenyan government authorities in their drive to register every citizen with a digital identity and work number.

The database could be stored at the clinic of the woman’s choice, with an undertaking that she must return to the same clinic where she registered for all subsequent check-ups and health issues.

Each time a patient returns for a check-up, she would use her fingerprint to authenticate her identity. This would enable the clinic to monitor the progress of the woman’s pregnancy and ensure she attended antenatal classes regularly, to educate her on issues of nutrition, hygiene, breastfeeding and baby care.

If she failed to attend one of the classes, the clinic staff would be alerted and may decide to visit her home to ascertain if problems had arisen. After childbirth, the baby’s immunisation schedule and growth could also be monitored and the data stored under the mother’s digital identity file. This data could also be accessed when the woman returned to the clinic for subsequent pregnancies.

Read our other scenarios on how digital identity could: